BIRMINGHAM, Ala. — As Alabama schools show continued improvement in test scores and have received national recognition for recent academic gains, Rep. Terri Collins, R-Decatur, says the state’s A-F report card for schools should evolve as performance improves.

House Bill 396, sponsored by Rep. Terri Collins, R-Decatur, would overhaul how Alabama’s public K-12 schools are graded, placing greater emphasis on student growth, particularly among the lowest-performing students, and on whether high school graduates are truly prepared for college or careers.

Collins, who sponsored the original A-F school grading law in 2012, said accountability systems must evolve as schools improve or risk losing their meaning.

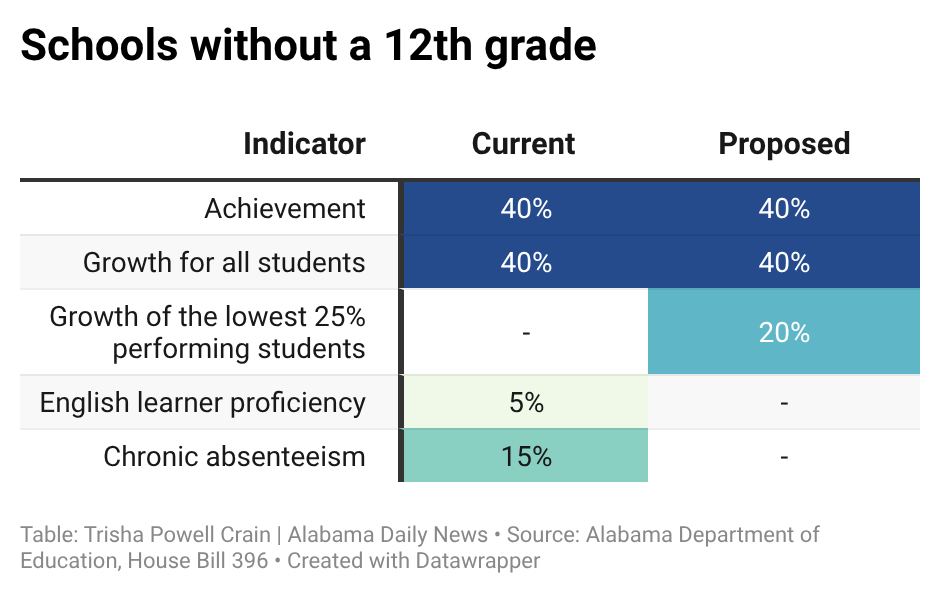

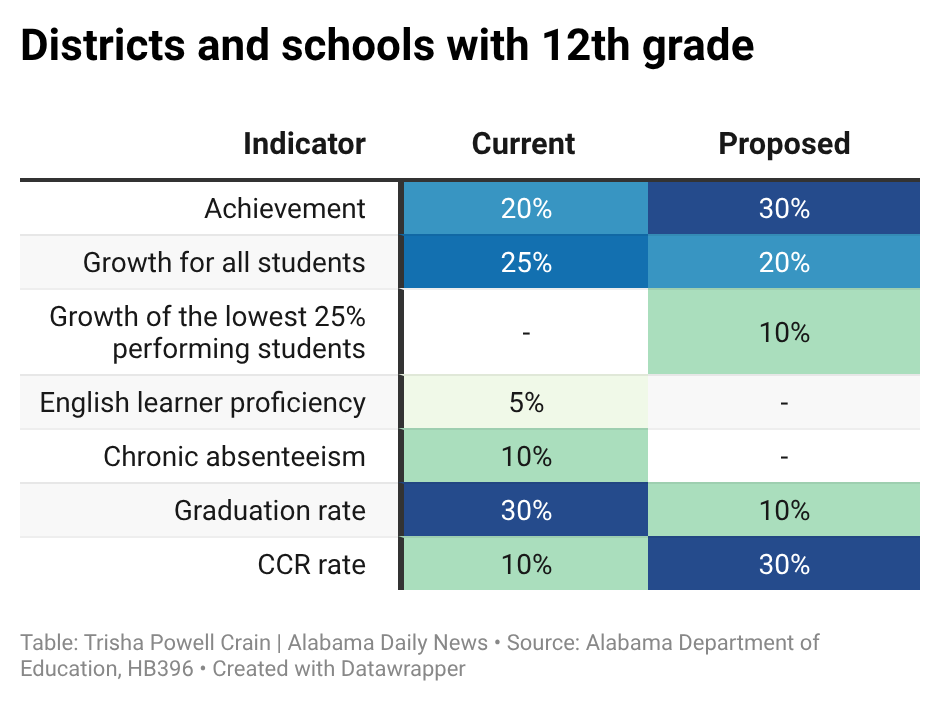

Under current law, schools are graded using a mix of achievement, growth, and other indicators. House Bill 396 would shift how much each indicator counts toward a school’s final grade.

The changes place a heavier emphasis on academic growth – especially for the lowest-performing students – while reducing the weight given to graduation rates and removing chronic absenteeism and English learner progress as graded indicators.

“Every school has a bottom 25% of achievers,” Collins said. “It doesn’t matter whether they’re English learners or not – growth matters. And we should be paying attention to that.”

For schools without a 12th grade, academic achievement and overall student growth would each account for 40% of a school’s grade, with the remaining 20% tied to growth among the lowest-performing students.

For districts and schools with a 12th grade, the bill would increase the weight given to college and career readiness to 30% – up from 10% – while reducing the weight of graduation rates from 30% to 10%. Academic achievement and growth would continue to factor heavily, along with a new measure focused on the lowest-performing students.

While the bill removes chronic absenteeism from the grading formula, Collins said she would still like to see it displayed on school report cards.

“I think parents and communities still need to see it,” she said. “It just doesn’t have to be part of the grade.”

The bill would not change the state’s existing college and career readiness indicators, which include ACT benchmarks, Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate coursework, dual enrollment, WorkKeys scores, industry-recognized credentials, apprenticeships, and work-based learning.

Beginning with this year’s graduating class, all high school students are required to earn at least one college or career readiness indicator to receive a diploma.

“Measuring something shows that you have a priority and a focus on it,” Collins said. She said the new report card weights would keep schools’ attention on achievement, growth, and preparation for college or careers.

One of the bill’s most consequential provisions would require the state to automatically raise its grading scale if school performance improves broadly.

If at least 60% of public schools earn an A or B in a given year, the 100-point grading scale would be raised by 10 points the following year – meaning, for example, that a score of 90 would become a B instead of an A.

On the 2025 report cards, 28% of schools earned A’s and 39% earned B’s, well above that threshold.

Collins said she had hoped the State Board of Education would raise the bar voluntarily as scores improved, but that has not happened.

“I truly hoped the board would do it on its own,” she said. “But if we don’t require the bar to move, eventually the grades stop meaning what they’re supposed to mean.”

Collins has long pointed to Florida as a model for how accountability systems can drive continuous improvement.

“I passed this law in 2012 because I watched Florida move from the bottom 10% of states to the top 10% in about a decade,” she said. “That didn’t happen by accident.”

Beyond letter grades, HB396 would require the state to begin reporting on what happens to students after high school as part of an annual return-on-investment report to lawmakers.

Those outcomes would include postsecondary enrollment and persistence, military enlistment, industry credentials earned, median income within six years of graduation, and employment in high-wage, high-demand fields.

“We owe it to taxpayers and families to know whether students are truly prepared — not just to graduate, but to succeed after graduation,” Collins said.

The bill would also create a standing Accountability Council, overseen by the state superintendent, with members appointed by the governor, legislative leaders, and education organizations. The council would be required to review the report card system and ROI data annually and make recommendations for changes.

Collins, who is not seeking re-election, said HB396 represents the next step in work she began more than a decade ago.

“We’ve never lifted our bar,” she said. “And I think our students deserve that.”

Alabama Daily News reporter Trisha Powell Crain served on the Accountability Task Force that helped determine the measures and weights used on the original set of school report cards.