They burned your office,” a breathless voice said at the door.

The air outside still smelled like smoke and hot paper.

Memphis was quiet in the way a threat waits.

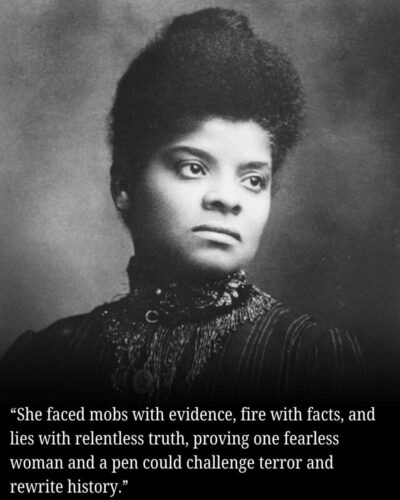

Ida B. Wells did not sit down.

She did not cry.

She gathered what could not be burned.

Facts.

She was born in 1862 in Mississippi, during the Civil War, which was still raging.

Her parents had been enslaved.

Freedom arrived loud and unfinished.

Yellow fever claimed the lives of her mother and father when Ida was sixteen.

The house went silent.

She became an adult overnight, raising her siblings on a teacher’s pay that barely stretched.

Grief had no time to settle.

She learned early how power worked.

Who was heard?

Who was pushed aside?

In 1884, a train conductor told her to move to the segregated car.

She refused.

Hands grabbed her.

Her dress tore.

White passengers stared as she was thrown from the train.

She sued the railroad and won, briefly, before the decision was overturned.

The lesson was sharp and clear.

Justice could be reversed.

But words could travel.

Ida turned to journalism.

Ink stained her fingers.

Presses clattered late into the night.

She wrote with a precision that cut through lies like glass.

Then came the lynchings.

Friends of hers were murdered in Memphis in 1892, dragged from jail and killed by a mob.

The city claimed it was about crime.

Ida looked closer.

She counted.

She compared.

She followed rumors until they collapsed under evidence.

The truth was uglier and more dangerous.

Lynching was terror.

Economic punishment.

Control.

Often triggered by Black success, not crime.

She printed the facts anyway.

That is why the mob came.

They smashed her newspaper office.

They warned they would kill her if she returned.

So she left Memphis, carrying notebooks heavy with names and numbers.

She did not go quiet.

She went louder.

She traveled through the South, then the North.

Lecture halls smelled of gaslight and damp coats.

Some audiences applauded.

Others hissed.

White newspapers called her reckless.

Officials called her a liar.

They said a woman, a Black woman, could not be trusted with such claims.

They never disproved her data.

In Britain, she spoke to crowds who leaned forward in shock.

She forced international attention onto American violence.

The pressure embarrassed the nation.

That made her enemies multiply.

Back home, she kept writing.

Pamphlets.

Articles.

Reports that read like indictments.

She named sheriffs.

She named towns.

She refused anonymity.

She married lawyer Ferdinand Barnett and moved to Chicago.

Motherhood arrived.

So did more work.

She wrote between feedings and meetings, refusing to choose silence for safety.

She fought segregation in schools.

She challenged white suffragists who wanted votes without justice.

When marches excluded Black women, she stepped into the line anyway.

Later, she helped found the NAACP, even as disagreements pushed her to the margins again.

She was used to that.

Institutions like comfortable voices.

Ida was not comfortable.

Threats never stopped.

Money was always tight.

Recognition came slowly, if at all.

She died in 1931, without the protection of the laws she had demanded.

But the record remained.

The numbers she preserved still speak.

The pattern she exposed still explains headlines.

Ida B. Wells matters now because she proved something terrifying to power.

That truth does not need permission.

That journalism can be an act of survival.

She showed that facts, when carried by courage, can cross oceans and centuries.

That a woman with a pen can stand against a mob.

That silence is a choice, and she never chose it.

The office burned.

The city threatened her life.

But the evidence walked out with her.

And it never stopped testifying