Alabama Education Policy Center releases report on STEM in Black Belt’s k-12 schools

BY: EDDIE BURKHALTER

Poverty and teacher shortages are drivers for lagging science and math proficiencies in Black Belt schools, the report finds.

There’s expected to be a 10 percent increase in the STEM field jobs by 2030, but students in Alabama’s Black Belt aren’t being prepared to get those science, technology, engineering and math-related jobs nearly as much as students elsewhere in the state, according to a brief released today.

That brief, titled “K-12 STEM Education in Alabama’s Black Belt” and published by the University of Alabama’s Education Policy Center, looks at how students in Black Belt schools do in math and science, what impacts those outcomes, and ways to improve them.

“Black Belt schools average less than half the math proficiency of non-Black Belt schools, with 11 percent compared to 23 percent,” Garrett Till, a student in the Masters of Public Administration program at the University of Alabama who helped research and write the report, told reporters during a briefing Monday.

None of the top 10 math proficient counties are in the Black Belt, but they account for nine of the bottom 10, and 18 of the bottom 20 counties, according to the brief.

“Of those 9 poorest performing Black Belt counties, 8 are majority-minority counties, and the bottom 2, Lowndes and Bullock counties, score below 1% math proficiency,” the report reads. “Only one of the 25 Black Belt counties, Lamar County, exceeds the state’s math proficiency average of 21.5%.”

Black Belt students scored similarly on science proficiency, with 22 percent showing proficiency compared to 36 percent for non-Black Belt schools.

Graduation rates among Black Belt schools were closer in line with those in other areas of the state, researchers found, with an 87 percent graduation rate compared to a 90.6 percent rate elsewhere in the state.

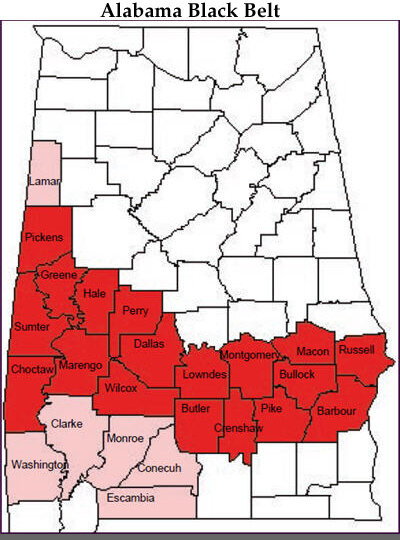

The center defines the Black Belt as consisting of 25 counties in the southern central and western areas, which includes all of Alabama’s majority-minority counties.

Authors of the report wrote that a factor affecting STEM education in the Black Belt is the shortage of teachers, especially highly trained teachers. Black Belt schools rely much more heavily on teachers who have emergency certification, meaning they have a bachelor’s degree but no training in the subject matters they teach.

The report notes that some counties, including Perry and Marengo counties, have approximately 80 percent of their math and science teachers teaching without full certification.

“Overall, more than 7% of all of teachers in Black Belt schools are emergency certified, compared to less than 2% among non-Black Belt K-12 teachers,” the report states.

“I’m not shocked by what I’m seeing,” Julie Swann, a UniServ director for the Alabama Education Association, said during the briefing, adding that the teacher shortage is real in Alabama.

“We’re gonna have to see more loan forgiveness, quite honestly, from the federal government to attract people to our rural counties. There’s going to have to be some more money,” Swann said.

Sean O’Brien, the primary author of the brief and another in the Masters of Public Administration program, discussed poverty’s impact on STEM education in the Black Belt.

“Poverty is now considered one of the most prevalent indicators of academic achievement. Poverty across the state the average statewide poverty rate is 15%. While Black Belt, the average in the black vote is 22%.

The most impoverished counties, including Bullock or Perry, rank worst or near worst in math and science, while low-poverty counties like Shelby and Baldwin have some of the state’s highest proficiency rates, the brief states.

Poor STEM educational outcomes aren’t just a Black Belt problem, however. Less than 25 percent of students statewide meet the benchmarks on the math and science portions of the ACT, O’Brien said.

The lower proficiency scores in the Black Belt may not be the result of school funding, however. Blac Belt schools spend approximately $800 more per pupil than non-Black Belt schools, O’Brien said.

“So it’s clearly not just a problem of spending on the school’s part. It’s poverty in the surrounding community. It’s the shortage of teachers,” O’Brien said.

Tuesday’s report was the second in a series of studies on the Black Belt, slated to be released by the center in the coming weeks. Other studies will focus on educational attainment and community college, poverty and housing market, mean worker commute time and infrastructure, goods versus services GDP, and profiles of Black Belt community leaders.

The first report in the series, which looked at COVID-19 in the Black Belt, was published last week.

The “Black Belt 2022” series is a follow-up to the center’s “Black Belt 2020” series of reports, which looked at First Class Pre-K in the Black Belt, labor force participation, unemployment, internet access, access to healthcare, and how to define the Black Belt.